Lecture: Colonialism, Capitalism and Human Rights

This was delivered as part of an undergraduate course called POLS113 Human Rights in the Political Science Department of Australian National University (that thankfully encouraged a critical analysis of international human rights discourse and practice, and the space to voice perspectives that are not often accepted in the field).

Introduction

I want to start by acknowledging that we are on Ngambri and Ngunnawal country, and pay my respects to elders past and present. This always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Today’s topic—colonialism, capitalism and human rights—goes to the heart of the question of who is and who is not human when it comes to international human rights? And how have human rights coexisted and co-evolved with colonialism and slavery?

The challenge of talking about colonialism and slavery is balancing the need to tell the truth about historic and present day injustices, whilst also finding space to somehow also move beyond formulations of domination, subjugation and extraction. A friend of mine Temi Lasade (an incredible researcher on Black women’s friendships online) recently shared this quote with me:

I love this quote because it reminds us that whilst we can’t invisibilise or diminish the pain of our lives and ancestral histories, we must also create liberatory narratives and imaginaries where Black, Brown and colonised populations get to experience joy, healing, care, rest, fulfilment, beauty, connection to the land and waters of country, spirituality.

So with that said, let’s journey through histories of domination, subjugation, and extraction but leave lots of space in our tutorials for discussion about resisting colonialism in all its forms and imagining different futures we can aspire to. I am coming from a queer, trans, Tamil migrant perspective, and also someone who is a settler on stolen land who myself benefits from ongoing settler colonialism.

Settler colonialism

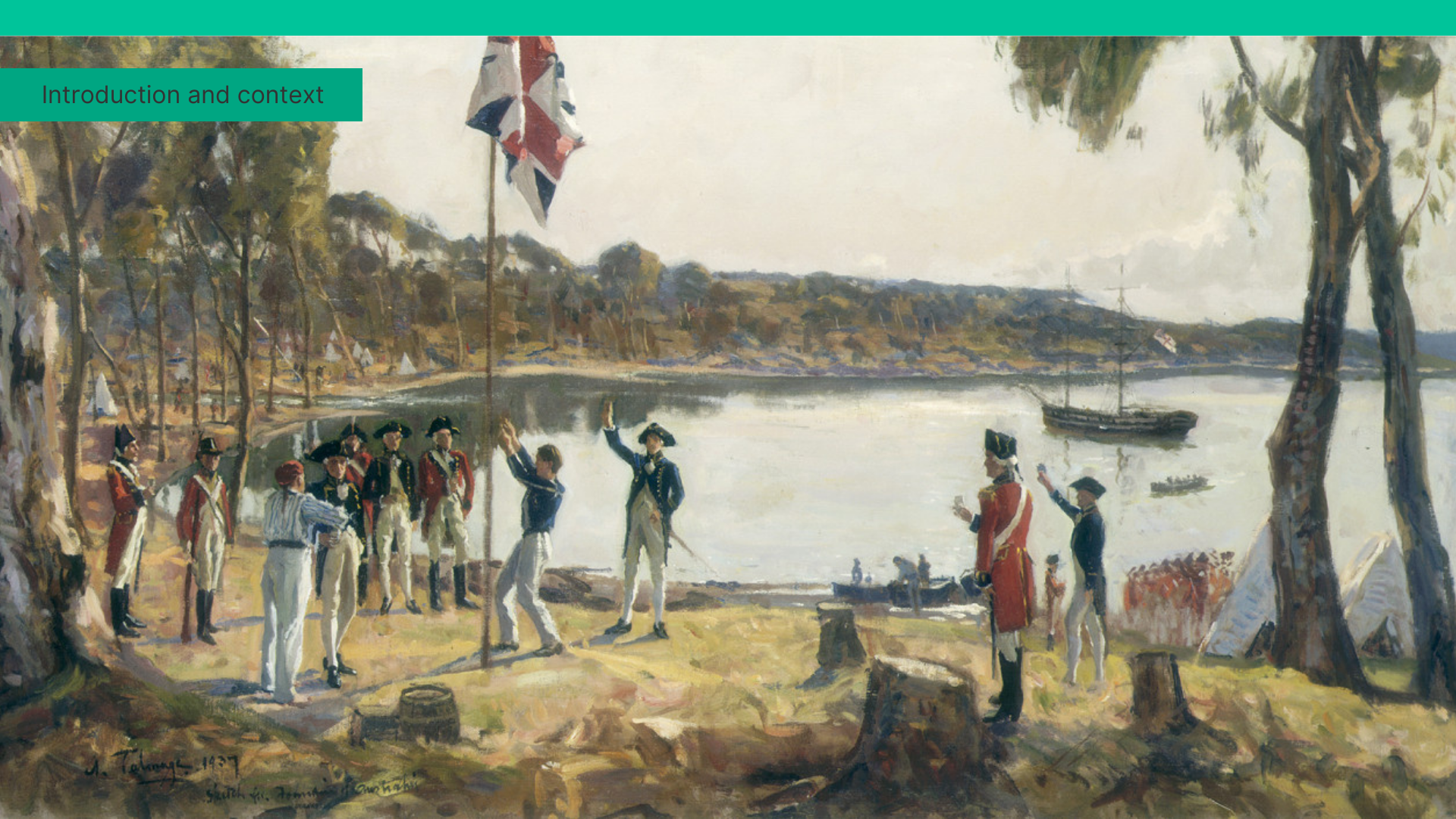

Settler colonialism is not a historical, but an ongoing structure in so-called Australia (Glenn 2015; Seamster and Ray 2018). Aileen Moreton-Robinson, a Geonpul woman and academic, explains (in one of her seminal texts, The White Possessive, 2015) there is no such thing as ‘post-colonial’ in the context of Australia, given that the settlers never actually left. In fact many global south scholars problematise the use of the term postcolonial even where formal processes of decolonisation occurred, because of the persistence of colonial dynamics which speak about more as we go.

Since invasion in 1788, British invaders claimed the land under the legal fiction of terra nullius—land belonging to no one—placing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders people in a ‘state of homelessness’ (Moreton-Robinson 2015: 16). Then the colonisers began a genocidal campaign of massacres, land theft, assimilation, removal of children from families, and erasure of language and culture (Moreton-Robinson, 2015). As Moreton-Robinson says, First Nations people were ‘systematically dispossessed, murdered, raped, and incarcerated the original owners on cattle stations’.

The formation of Australia as a nation-state was based on a racialised hierarchy of citizenship, where citizenship rights and associated benefits were based on whiteness. Legislation and state policies served to exclude Indigenous people from participation as citizens (Moreton-Robinson 2015: 13). Further racial exclusion was enacted through banning all non-white migrants from entering the country. The “White Australia policy“, which enshrined this racial hierarchy of citizenship in law, only officially ended in 1973. Although Indigenous people attained citizenship in the late 1960s but, they continue to experience exclusion from Australian society, comprising more than one-fifth of all homeless people (Moreton-Robinson 2015; AIHW 2019), and 28% of the imprisoned adult population (Anthony 2017), making them proportionally the most incarcerated population globally.

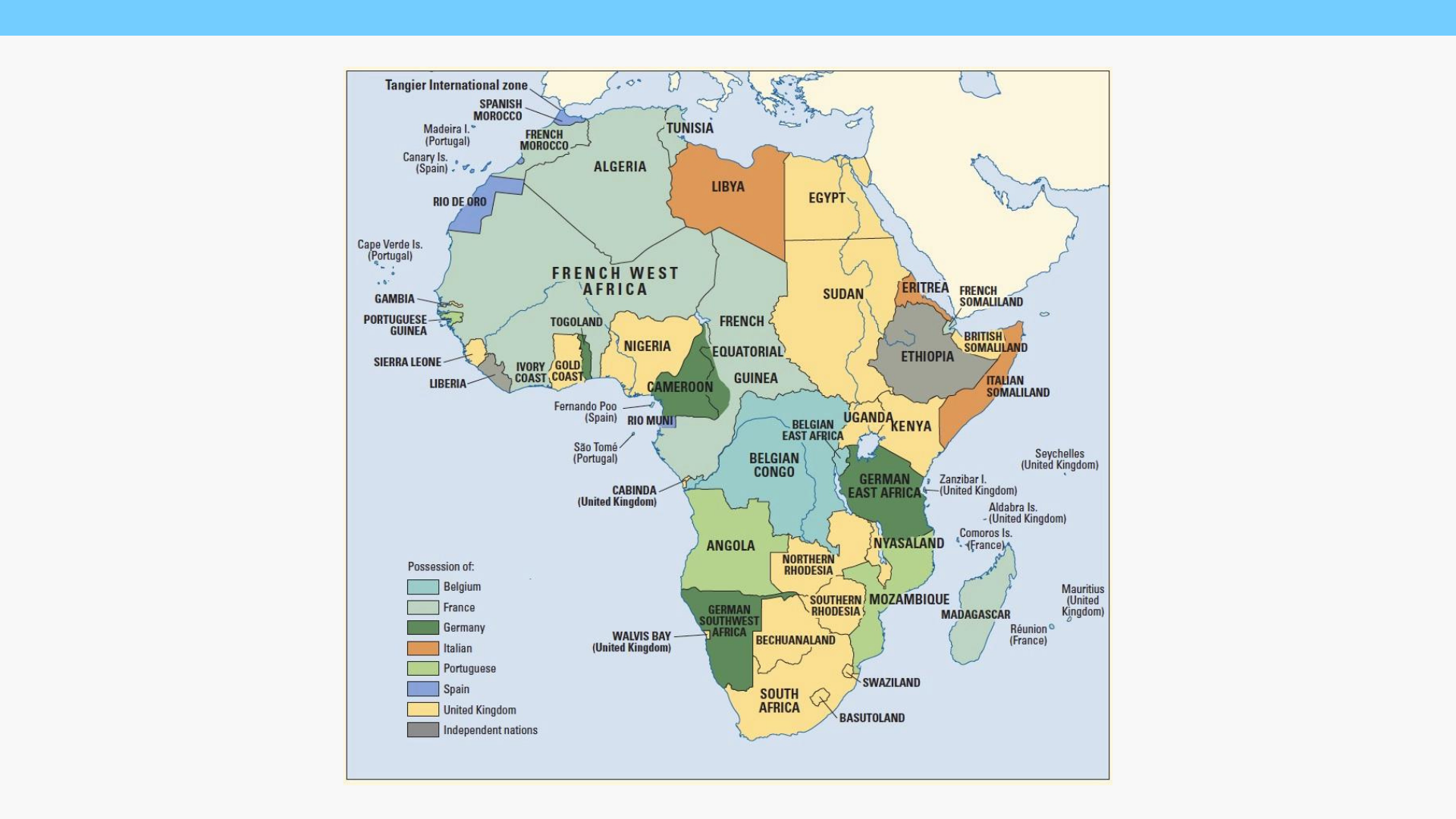

Zooming out to colonialism at a global scale, it typically refers to the 400 year post-Renaissance European colonial project (in particular by the British, Dutch, French, German, Belgian, Portuguese and French). Colonial practices predate European colonialism, however this period was particularly influential in shaping the modern world. At the height of the British Empire in 1913, they ruled approximately a quarter of the world’s population, to give you a sense of scale.

European colonialism and capitalism

Colonialism and capitalism are inextricably intertwined. Through colonialism European nations grew their wealth by deploying military force to establish an economic system, in which colonies in the global south provided raw materials and slave labour. This expropriation of land and bodies for capitalist expansion, is a process known as ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Harvey 2004).

British colonialism powered the industrial revolution and the expansion of capitalism (1750-1850) (Ashcroft et al). The industrial revolution created a huge demand for raw materials like rubber, metals and timber. Also tea, coffee, sugar, oil were in demand by a growing upper class. The vehicle at the centre of this accumulation of wealth were the world’s first multinational corporations, such as the East India company.

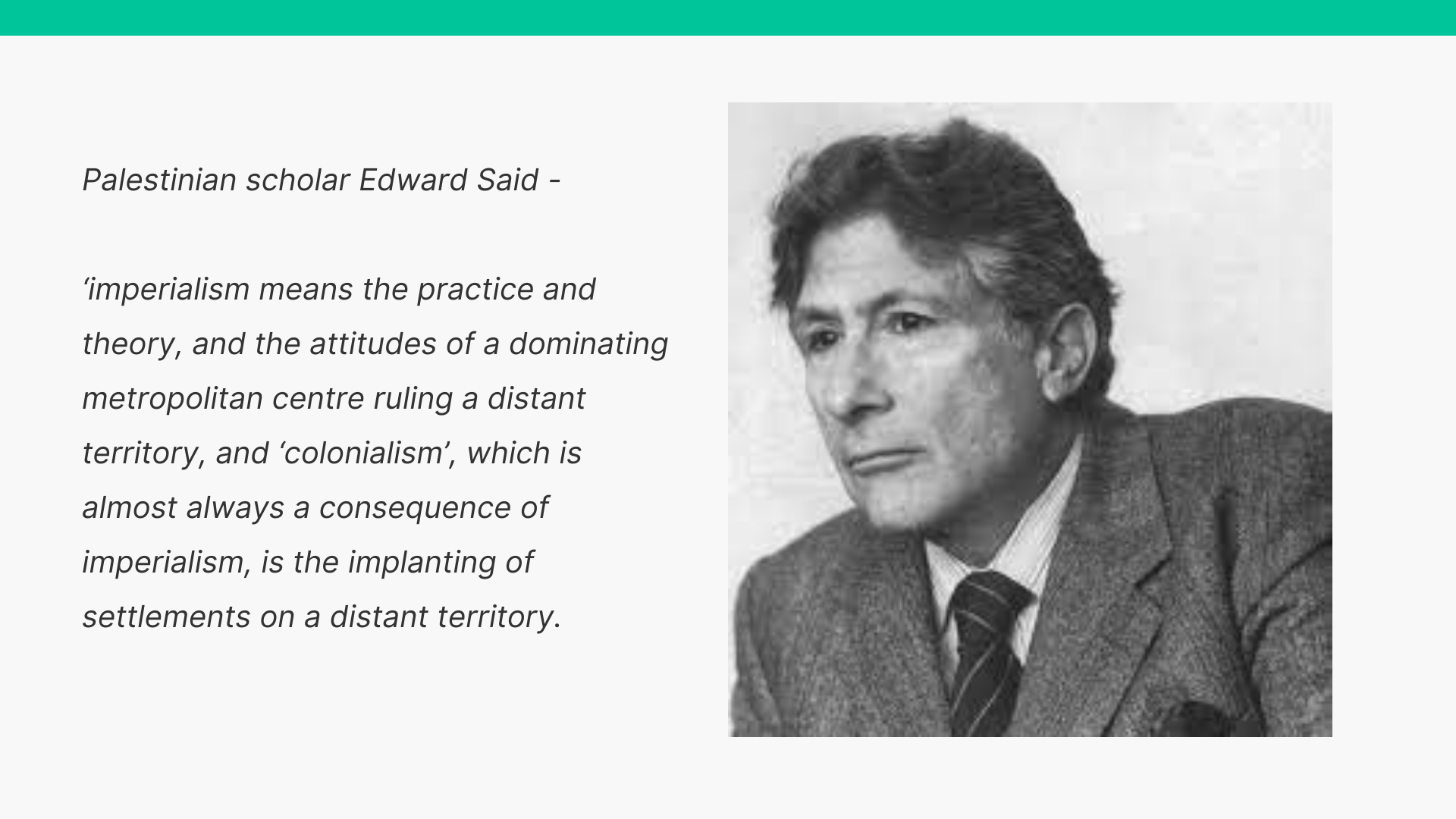

Let’s look at the difference between colonialism and imperialism.

- Both colonialism and imperialism refer to the exploitation of one group by another.

- Colonialism specifically refers to the establishment of colonies for the purposes of this exploitation.

- Imperialism (and neo-colonialism) can refer to the imposition of values, cultures, ideologies and religions by a dominant group, onto a subjugated group, and can occur without colonialism.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade

The African continent was rich in natural resources, such as palm oil, tea, coffee, sugar, cocoa, timber and tobacco. This created the conditions of what is referred to as the ‘scramble for Africa’, which refers to European countries’ rush to carve up Africa amongst themselves between 1881-1914. In 1870, 10% of the Africa continent was colonised. By 1914, 90% was colonised.

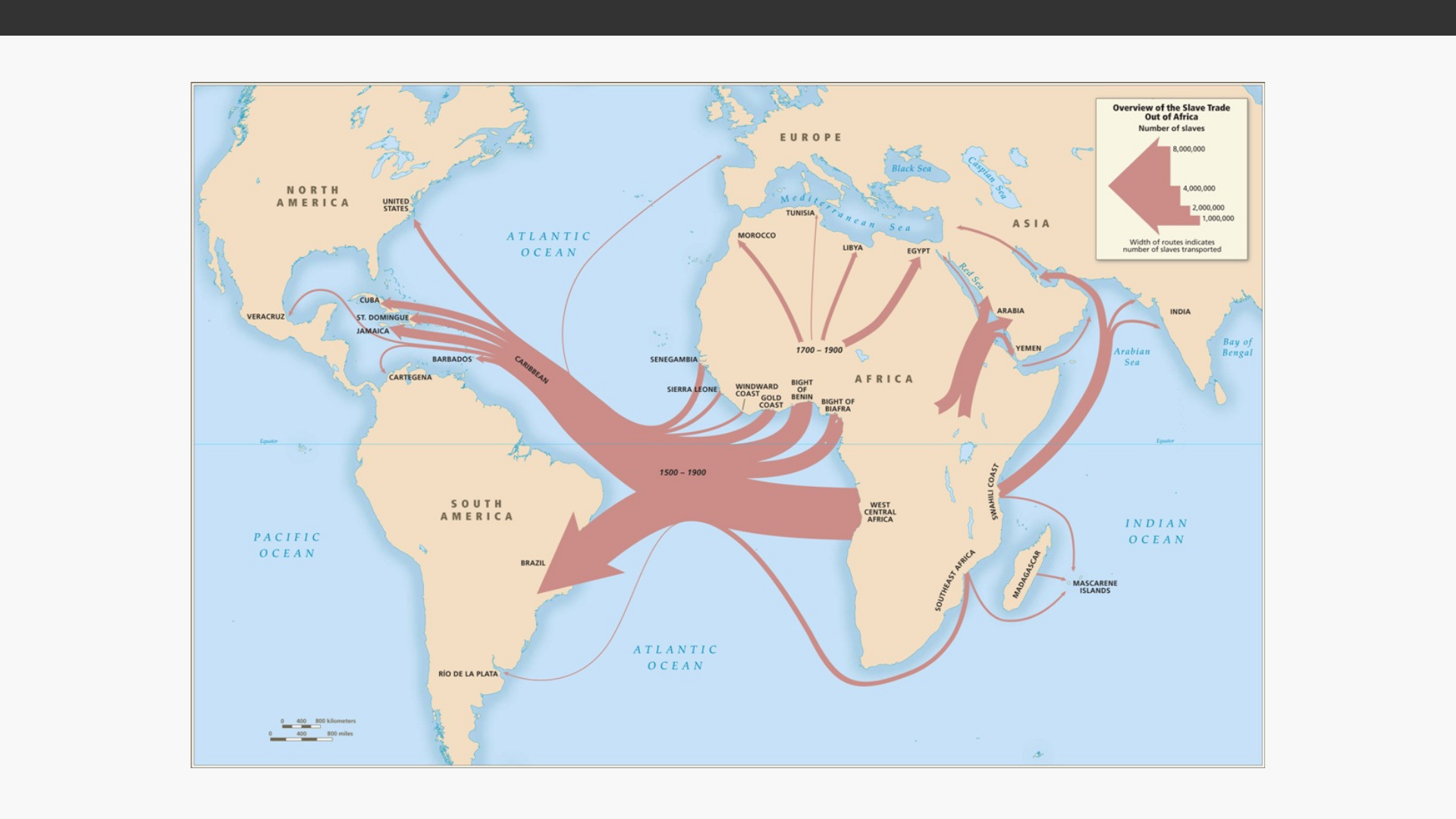

European institutionalisation and commercialisation of slavery in the late sixteenth century provided them with an endless supply of free labour. In 1503, Christopher Columbus developed a plan to buy and import black slaves from Africa to the Caribbean to work on plantations - this started 300 years of slavery. Over this time more than 12 million African slaves were brought to the Caribbean, Brazil and the United States. The Transatlantic Slave trade saw the commercialisation of slavery at an unprecedented scale. It was more industrialised, brutal and dehumanising than Greek and Roman practices of slavery. The Atlantic slave trade saw slaves as property with no rights or freedoms - slaved were completely dehumanised.

First Nations people in so-called Australia were also forced into forms of slavery and unfree labour through colonisation. Pacific Islanders were kidnapped or coerced to come to Australia and work, in a practice known as blackbirding. Labourers were also imported from India and China, and employed in various degrees of unfree labour. The well known Australian company CSR, which literally stands for Colonial Sugar Refining Company, Blackbirded (i.e. kidnapped) South Sea Islander labour in Queensland, and imported indentured labourers from India to Fiji (known as Girmityas) to deforest the land, plant, and cut the sugarcane, and build the mills.

Colonial racial hierarchies were the primary structuring principle of the capitalist world economy which laid the foundation for the lasting rift between parts of the world categorised broadly as Global North and Global South (Hoogvelt, 1997).

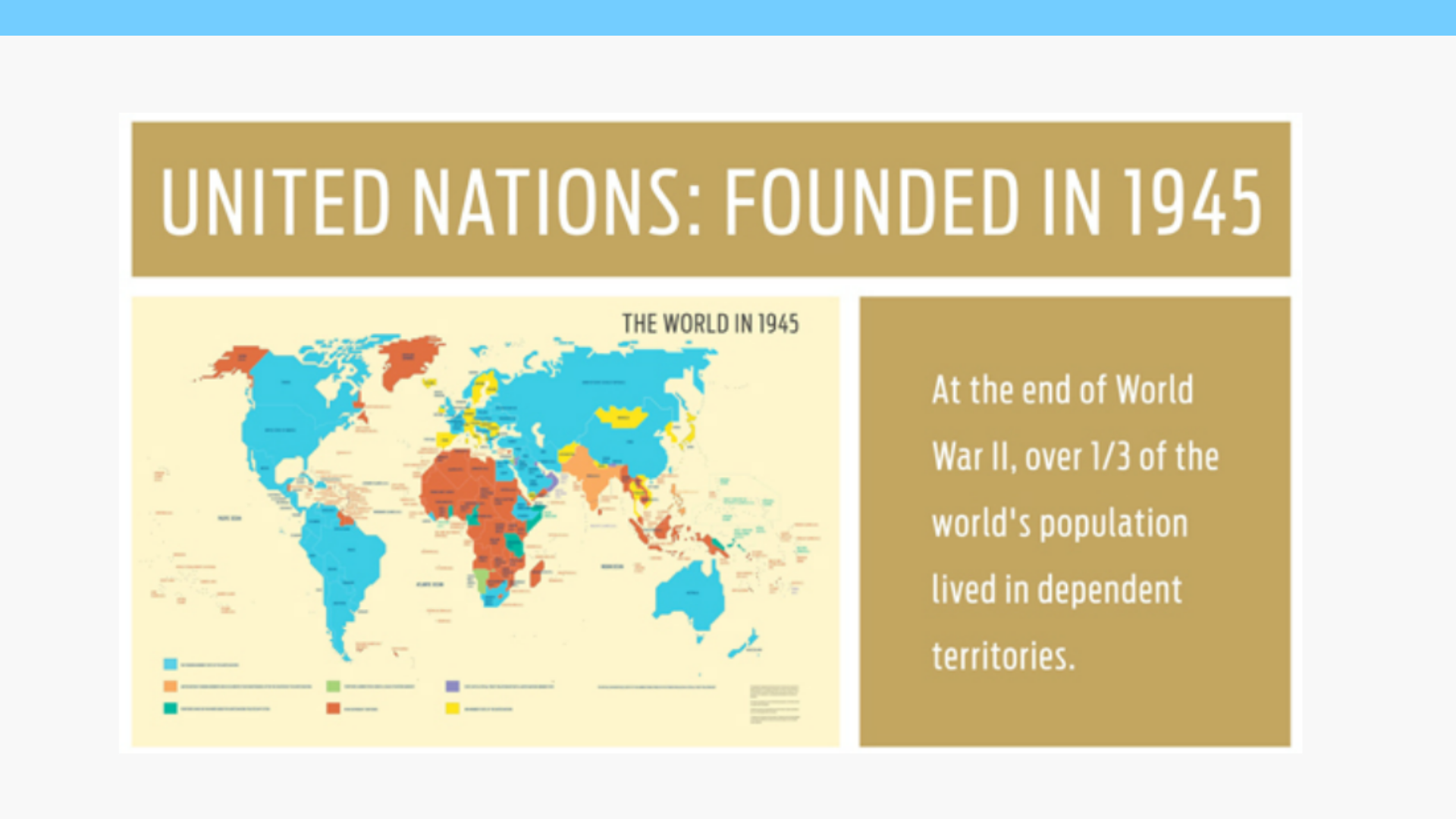

Colonisation was central to the spread of the modern nation-state and system of global governance. Membership to the UN is based on the idea of independent state-hood. The human rights system is intimately connected with the idea of nation statehood. When the UN was created there were only 51 member states, and now there’s 193. The majority of these new countries are former colonies of those other states.

Colonial constructs of race and criminality

How did colonisers get away with these practices?

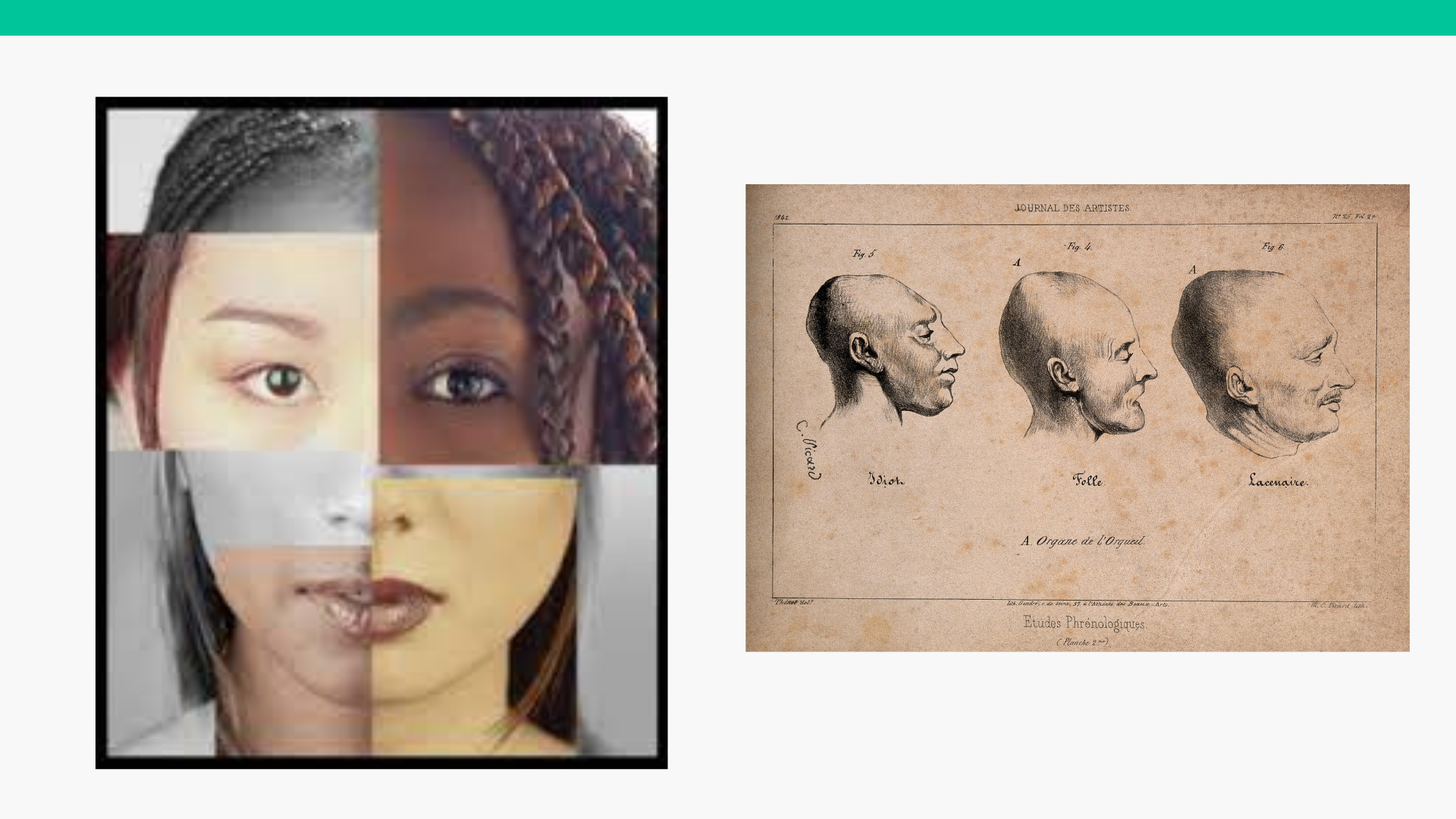

Constructions of ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ were a key part of colonial discourse. Narratives around race, racial difference and white supremacy were used to justify colonialism and the slave trade. “Scientific” racialised classification systems created by colonisers had their roots in Enlightenment epistemologies such as social Darwinism and eugenics. They presented race as an inherent biological phenomena, rather than as constructed. Whilst this is often dismissed or described as pseudoscience in literature, some argue that this diminishes the potency, power and widespread adoption of these views. This included phrenology and craniology - the study of shapes and sizes of people's skulls which was thought to correlate with disposition, intelligence and character traits.

Associated with the Enlightenment thinking were notions of how concepts of 'race' and 'progress' related to one another. According to critical race scholars Seamster and Ray (2018), there were two broad ways colonisers thought about this. Eugenists, for example, believed ‘that racial others occupied Europe’s past’—and argued that the eradication of so-called ‘lesser races’ constituted progress (Kendi 2016; Seamster and Ray 2018). Others thought so-called ‘wretched of the earth could perhaps, with great effort, be moved into the Western present’ (Seamster and Ray 2018: 319)—in other words, ‘civilized’. And this is how assimilationist policies were rationalised.

The key point I want to get across here is that just as race is constructed, so is the category of ‘criminal’. Race been instrumental in creating and reinforcing the social identities, divisions, and hierarchies that shape contemporary society (Gandy 1993; Lyon 2003). This is most apparent in the logics that construct the ‘criminal’. Colonial racial taxonomies formed the basis for the modern study of ‘deviance’, a core concept of the scholarly field of Criminology (Brown & Barganier, 2018). Deviance is based on a “constant division between the normal and the abnormal” (Foucault, 1977) so that groups can be “sorted by levels of dangerousness” (Feely and Simon 1994).

Harsha Walia, in her book Undoing Border Imperialism observes that 'criminals are never imagined as politicians, bankers, corporate criminals, or war criminals, but as a racialised class of people living in poverty. The word criminal becomes synonymous with dehumanising stereotypes of ghettos, welfare recipients, drug users, sex workers, and young gang members' (2013).

The criminalisation of migration intensified in the aftermath of the attacks of 9/11 in New York and Washington DC (Akkerman, 2016; Lyon, 2003). The construction and reinforcement of race-based categories (Finn, 2005) as a potential threat (for example, Arab and Muslim men) justified a suite of new global counter-terrorism policies, legislation and the strengthened power of police and intelligence forces (Pellerin, 2005).

In addition to racial categorisations, the sex and gender binary were also central colonial strategies for maintaining social hierarchies and structural power—allowing for the categorising, ordering and controlling society. We now understand that dividing billions of humans into categories of a man or a woman, male or female—is a social decision, a political choice, not a biological truth. Colonisation and white supremacy erased long documented legacies of people existing outside of the gender binary across the world.

This dark colonial history (and present) exposes how claims to universality and inclusion when it comes to human rights have co-existed with exclusion and subordination. The moment when Europe was in the midst of a struggle for liberty, equality and freedom, Europe’s ‘Others’ continued to be subjugated under the weight of colonialism and slavery.

Often discourses around colonialism categorise people into two group - either the coloniser and the ‘Other’, or the colonised. But in reality European colonisers worked closely with elite populations in the places they colonised to enable and enforce their rule. For instance in India, upper caste Indians in particular where deeply complicit in the British colonial regime.

Further to this, the colonisers gained control through dividing and ruling local populations. To use the example of the British in India again, they collected vast amounts of data on caste, religion, profession and age among other classifying characteristics across colonial India. This information was used to solidify inequities of the caste system, and increase religious tensions; the violent legacies of which are still being experienced today. That said, I don’t want to imply diminish the abhorrent violence of the caste system, even in pre-colonial India—although it is true to say these caste divides were strengthened.

In places like Sri Lanka, the British divided ethnic groups and pitted them against one another—including the Singhalese, Tamils, Muslims, the Burghers (mixed Dutch heritage), Malays, Tamils of Indian Origin (on tea plantations), Veddas. For instance, Jaffna Tamils, particularly high caste Christians were favoured over the Sinhalese majority for recruitment to the colonial bureaucracy. Then the vacuum left by the British post independence led to rising ethnic tension, a key factor that influenced events leading to the Tamil genocide. This is a common story in many global south nation states, and you will all be familiar with numerous examples.

Despite the fact that race is literally….a construction, we ourselves, as colonised populations can internalise these myths of white supremacy. This can lead to a belief in our own inferiority, physically, intellectually, and in other ways. This might look like: subscribing to euro-centric beauty standards, underestimate our skills and capabilities, or undervalue our language, culture, sciences and arts.

The UN, Human Rights and Decolonisation

So in 1945 (when the UN was established) and 1948 (when the UN declaration of Human Rights was drafted) most UN member states were colonial powers. Since 1945, 80 former colonies have gained independence.

As we’ve talked about, and as Susan Watz (2001) says, the drafting of the UDHR involved much debate over ‘the notion that fundamental freedoms must include the right to political independence [...these] efforts were resisted at every turn by colonial powers not yet persuaded that decolonisation was an idea whose time had arrived.'

This is discussed in depth in the Roberston reading, Saving Empire: The attempt to create non-universal human rights (2014), where he talks about how Great Britain, in its attempt to maintain the social relationships, legal conventions, and political structures of its empire, introduced a proposal for a colonial application clause. When inserted into an international treaty, this restrictive legal mechanism granted the colonial power the discretion to withhold the treaty from (or apply it to) any or all of its dependencies.

The colonial clause was a short paragraph or two of text, but it embodied a social ideology, a political system, and a legal framework. Robertson argues that debates between colonial and anticolonial factions over the right to self-determination (which appears prominently in Article 1 of both of the Covenants) tends to be highlighted in historical research, whilst the colonial clause was at least as important as those over self-determination.

The battle over the colonial clause was essentially a debate over the entire meaning of universal human rights. If the colonial powers had succeeded in placing colonial clauses in the IBHR, human rights would not be 'fundamental' to all humans.

Global hegemons also also fiercely resisted the inclusion of cultural genocide in the genocide convention because they quite rightly feared that is was too closely associated to their practices of settler colonialism.

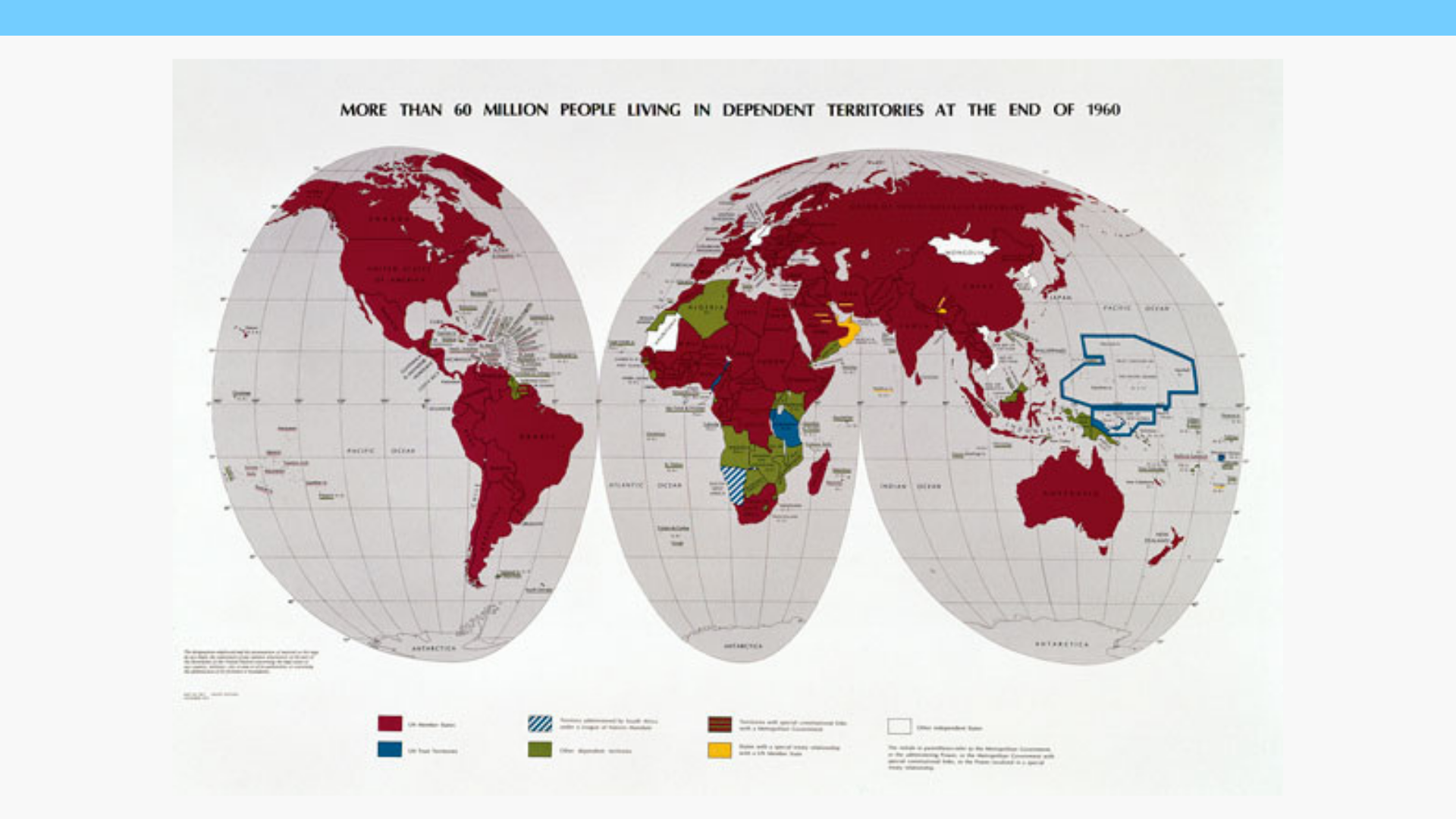

By the 1960s, the tide had turned, as per the timeline below:

1960 - Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. Affirmed the right of all people to self-determination and proclaimed that colonialism should be brought to a speedy and unconditional end.

1962 - Special Committee on Decolonisation was established to monitor its implementation.

1990 - UN names this the ‘International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism’

2001 - Then in 2001 there was ‘The Second International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism'

2011 - Then, in 2011, there was, you guessed it, ‘The Third International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism'

Neocolonialism

An important concept to understanding the persistence of colonial dynamics, politically and economically, is neo-colonialism.

The term was coined by Kwame Nkrumah (1965), the first President of Ghana, to describe the way in which previous colonisers continue to exert control and influence over previously colonised peoples.

Nkrumah said that this form of exploitation was more insidious and harder to detect. Neo-colonialism might take the form of ‘diplomacy’, foreign aid, development agendas, economic sanctions, etc. He questioned whether foreign aid ever be completely self-less, or are their gains the donor country is seeking. Neo-colonialism frees the notion of colonialism from the physical presence of colonies.

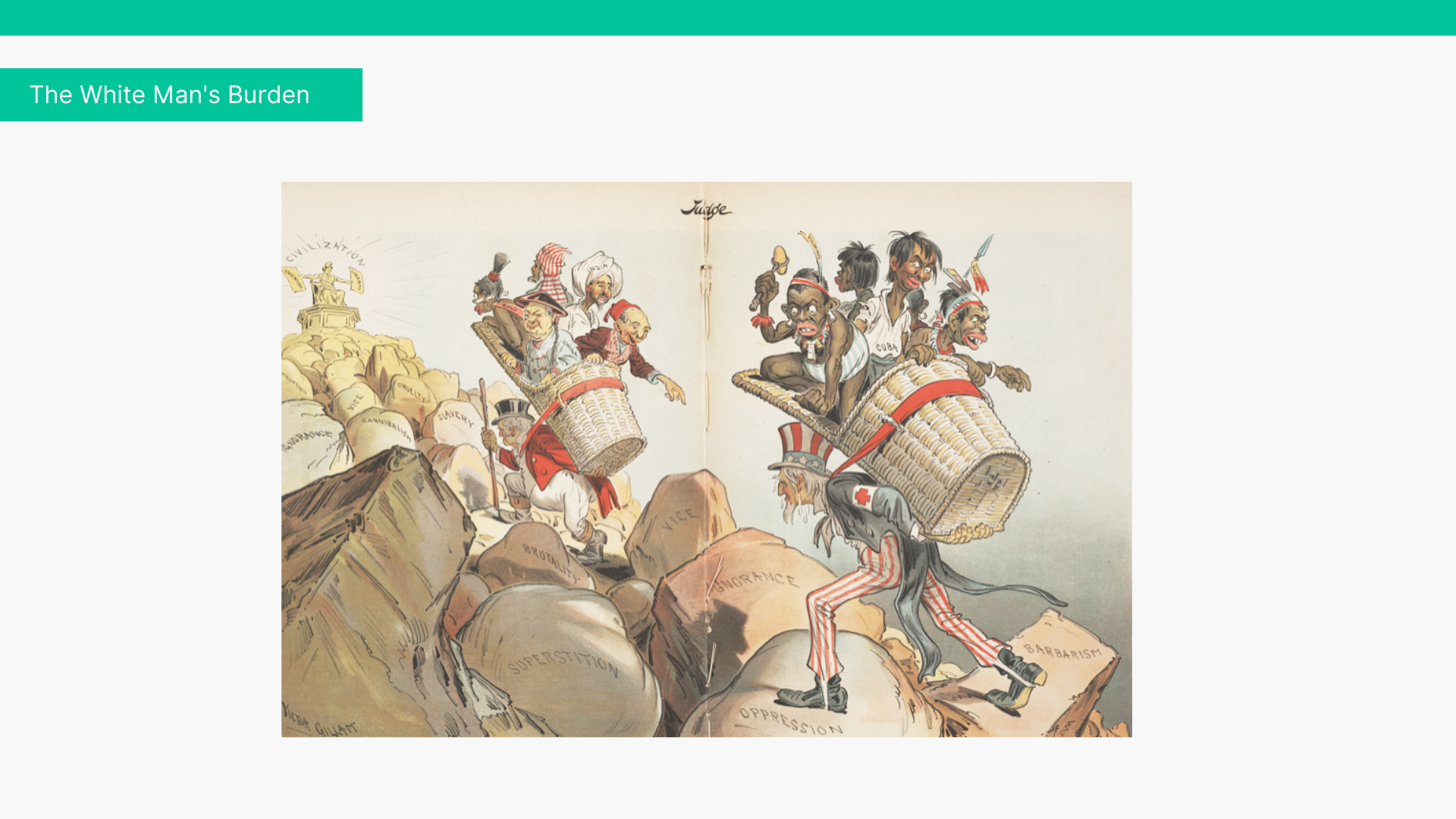

Here through the mention of foreign aid, Nkrumah (1965) is alluding to the concept of humanitarianism. Yesterday in some tutorials we talked about the concept of the ‘White Man’s Burden’. The phrase refers to a 1899 poem by Rudyard Kipling’s Hymn to U.S. Imperialism, British novelist and poet that captured a racialized notion of the burden of civilising the rest of the world became a widespread euphemism for imperialism. Baxi (2008), one of the readings argues that the universality of human rights can only extend to the non-European other (as seen in Chapter 2) upon the successful performance of the mission of the ‘White Man’s Burden’.

The dark side of human rights

Other so-called ‘postcolonial’ critiques of human rights, such as Kapur (2006) also argue that ‘International law coupled with its humanitarian zeal was structured by the colonial encounter and its distinction between the civilised and uncivilised’.

Kapur’s argument is that deeply embedded in conceptualisations of human rights are assumptions and arguments about civilisation, cultural backwardness, racial and religious superiority. She says—'this dark side is intrinsic to human rights, rather than something that is merely broken and can be glued back together.’ In order to make possible a future where human rights no longer dehumanises colonised people, it is critical to ‘revisit the colonial encounter…. in order to understand the limitations and possibilities of human rights in the contemporary period. She argues that ‘it is essential for human rights advocates to embrace this history.’

Neoliberalisation

The other phenomena occurring in the global economy during the period of decolonization, was neoliberalisation.

Neoliberalisation is a contested concept but for the purposes of this discussion, we can think about neoliberal economic policy (of the 1970s) as ushering in an era of free trade, open markets, privatisation, deregulation, and an expansion of the role of the private sector (Fraser, 2003).

In the Global South neoliberalisation weakened states through the opening of markets to powerful foreign firms. The US established its position as a global empire through coercing Global South countries to accept development loans channelled through the IMF, World Bank, USAID, and other foreign 'aid' organisations. When debts could not be repaid large corporations deployed fraudulent and violent tactics to force Global South states to acquiesce to US political pressure (Ayazi and Elsadig, 2019).

Whilst this was a period of economic globalisation with the freer flow of goods and information (i.e. borders of economic integration) (Marx, 2005; Pellerin, 2005), it simultaneous resulted in the securitisation of borders (i.e. borders of security) in regions where economic integration was moving ahead, largely in the Global North (Pellerin, 2005).

These two analytical logics were linked. Border security measures such as the militarisation of borders, immigration detention and deportation were predominantly targeted at impoverished and colonised communities from the Global South, despite the fact that Global North actors were in part drivers of this mass displacement (Walia, 2013).

Neoliberalisation in the Global North manifested in cuts to, and the privatisation of state-furnished public services, from public utilities, education, and health care, to social welfare, public space, and other services (Ayazi and Elsadig, 2019). The withdrawal of the state from public services further magnified its 'law, order and security' function. This is important context for what is to follow.

Neoliberalisation, colonialism and human rights

We talked yesterday about Moyne and his book The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History (2010), where he argues that, due to the ruins of earlier political utopias, such as the soiled political dreams of revolutionary communism and nationalism, individual rights and international law became an alternative to popular struggle and bloody violence. This is why, in his view, human rights didn’t take off as a concept until the 1970s. He observes that in the 1940s barely any NGOs used human rights discourses. For instance, Amnesty International, went from being a unknown fledging group, to winning the Nobel Peace Prize for its work in 1977.

He says, ‘even politicians, most notably American president Jimmy Carter, started to invoke human rights as the guiding rationale of the foreign policy of states. And most visibly of all, the public relevance of human rights skyrocketed, as measured by the simple presence of the phrase in the newspaper, ushering in the current supremacy of human rights.'

There are some other scholars who have a different opinion to Moyne about why this was the case. Notable Radha D’Souza and Jessica Whyte. Both of their work maps the historical conceptual relationship between human rights and neoliberalism (Whyte, 2019).

Jessica Whyte in her book, The Morals of the Market (2019), offers a detailed account of how prominent neoliberal thinkers (such as Frederick Hayek, part of the Mon Pelerin society) who saw postcolonial state demands for sovereignty and economic self-determination as threats to Western 'civilisation', co-opted human rights as a tool to preserve the market order, and the global division of labour (i.e. Global South labour continues to be extracted for the Global North), by tying it fundamentally to the free market, and using it as a weapon against anticolonial projects all over the world. Rather than rejecting rights, they developed human rights as tools to depoliticise civil society, protect private investments and shape liberal subjects.

Both Whyte and D’Souza argue that when it became inevitable that states would pursue political sovereignty, neoliberal forces aimed to ensure that economic sovereignty could not be achieved. The privatisation of natural resources in the Global South meant that the physical presence of colonies was no longer necessary for exploitation, particularly with the growth of multinational corporations.

Whyte (2009) documents how neoliberal thinkers and NGOs such as Amnesty International and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) framed 'freedom' as a human right by linking it to market freedom from state control. Whyte explains that the NGO embracement of neoliberal human rights gave a 'progressive gloss' to the anti-Global South agenda of the IMF and the World Bank and others who supported their policies of abusive austerity (Whyte, 2019).

Conclusion: consider these statements

Based on everything you have heard today, do you think human rights a hegemonic or counter-hegemonic discourse/ideology?

The end